Register as an organizer

Click the button below and finish your organizer registration, or fill out the form and we will be in touch to assist you.

When you're looking to book an artist, understanding the financial side of things is super important. Deals can get complicated fast, with talk of guarantees, percentages, and all sorts of other terms. This guide breaks down some common deal structures and what they mean for both the artist and the person booking them. It's all about making sure everyone's on the same page and the money makes sense.

When you're talking about advances in music deals, the publisher or label isn't just handing over cash for nothing. There are usually strings attached, and these are called advance delivery requirements. Basically, it's what you, the artist, have to provide to earn that money. It's not always just about delivering a certain number of songs; sometimes, the quality or licensing status of those songs matters too.

Think of it like this: you might agree to deliver ten songs for your advance. But the deal might also say those ten songs need to be licensed for at least 75% of the statutory rate. This can get tricky, especially with new artists. If an album is released at a lower price point, the mechanical royalty rate you get paid is often cut in half. So, if your deal requires songs licensed at 75% of the statutory rate, but the label only pays 50% of that due to the album's pricing, the publisher might argue they don't owe you the advance, or at least not yet.

It's important to get clarity on how fractional ownership of songs counts. If you co-wrote a song and only own 50% of the publishing, that should count as half a song towards your delivery commitment, not a full song. Most standard contracts don't automatically account for this, meaning you might not get credit for songs you partially own, even though they still earn money.

Here’s a breakdown of common delivery requirements:

It's a good idea to build in protections for falling short of a target. Instead of an all-or-nothing situation, aim for a pro-rata payment. For example, if you're supposed to deliver ten songs and only deliver eight (80%), you should ideally get 80% of the advance, not zero. Publishers will often agree to this, but they usually insist on a minimum delivery threshold, like 50% of the target, below which no payment is made.

Understanding these terms is key to making sure you get paid fairly for your work. It's all part of the bigger picture when discussing merchandising agreements.

When you're talking about advances for artists, especially in music or publishing, you'll often hear about a "floor" and a "ceiling." Think of it like a safety net and a lid on how much money you can get for your next project, like a new album or book.

Basically, the floor is the minimum amount you're guaranteed to receive as an advance, no matter what. Even if your previous work didn't sell as well as expected, you'll still get at least this amount. It's there to give you some financial security and encourage you to keep creating.

On the other hand, the ceiling is the maximum amount you can receive. This is usually tied to how well your previous work performed. If your last album was a massive hit, you might get an advance closer to the ceiling. It's a way for the label or publisher to limit their risk while still rewarding success.

Here’s a simple way to look at it:

These numbers are usually negotiated upfront in your contract. They're calculated based on a formula, often a percentage of your previous earnings, but they're adjusted so they don't go below the floor or above the ceiling. So, if the calculation based on your sales lands somewhere in the middle, that's what you get. But if the calculation suggests you should get less than the floor, you still get the floor amount. And if it suggests you should get more than the ceiling, you only get the ceiling amount.

It's all about balancing risk and reward. The floor protects the artist from a bad sales period, while the ceiling protects the company from paying out too much if sales are unexpectedly huge, though often the ceiling is set quite high for successful artists.

For example, let's say an artist's contract states:

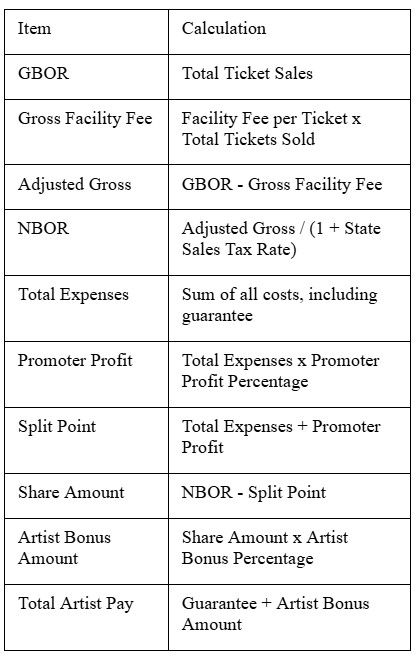

Alright, let's break down how a promoter profit deal actually works, step by step. It sounds complicated, but it's really about figuring out who gets what after all the costs are covered. Think of it as a way to share the risk and the reward.

First off, you need to know the total money brought in from ticket sales. That's your Gross Box Office Receipts, or GBOR. Then, you figure out the facility fee, which is usually a per-ticket charge for using the venue. Multiply that fee by the number of tickets sold to get your Gross Facility Fee.

Next, you subtract that Gross Facility Fee from the GBOR. This gives you what's called the Adjusted Gross. From there, you need to account for sales tax. If the tax is already included in the ticket price, you'll divide the Adjusted Gross by (1 + tax rate) to find your Net Box Office Receipts (NBOR).

Now, it's time to list all the expenses. This includes everything from venue costs and marketing to the artist's guarantee. Once you have your total expenses, you can calculate the promoter's profit. This is usually a percentage of the total expenses, as agreed upon beforehand.

Here’s a simplified look at the numbers:

So, the split point is the amount of money that needs to be made before any extra bonus money is paid out. Anything above that split point is then shared between the artist and the promoter, usually with the artist getting a bigger cut, like 85% or more. This bonus amount is added to the artist's initial guarantee, giving you the total amount the artist gets paid.

It's all about transparency. Both the artist and the promoter need to agree on how these numbers are calculated. Make sure every expense is accounted for and that the percentages for profit and bonus splits are clearly defined in the contract. This avoids any confusion later on.

When you're talking about how artists get paid, the payment schedule is a really big deal. It lays out exactly when and how you'll receive your money. This isn't just about getting paid; it's about managing your cash flow and knowing what to expect.

Different types of deals have different payment structures. For instance, in a commission agreement, you might get a portion of the payment upfront when the contract is signed, and the rest when the work is finished and delivered. It’s pretty common to split it this way, maybe 50% at the start and 50% at the end, but you can negotiate that. You'll want to be clear about the total cost, including any taxes or shipping, and how much of that comes at each stage.

For advances, especially in music publishing or record deals, the schedule can be more complex. You might get a chunk when you sign, another chunk when you deliver a certain number of songs or recordings, and then the rest as you hit other milestones. It’s not unusual to see payments broken down like this:

It’s also important to understand the concept of accounting delays. This is the time a label or publisher has to calculate and report sales and royalties. So, even if a sale happens in January, the money might not show up on your statement until months later, depending on the reporting frequency (monthly, quarterly, or half yearly) and the agreed upon delay.

The specifics of your payment schedule are usually laid out in the contract. Always read this section carefully and make sure you understand when payments are due and what conditions need to be met for those payments to be released. Don't be afraid to ask questions if anything is unclear.

A royalty style deal is pretty common in the music industry, and it works a bit differently than a profit share. Instead of splitting the profits after all costs are paid, you get a set percentage of the money that comes in, right from the top. This means you get paid based on gross revenue, not net profit.

Think of it like this, if a song makes $100, and your royalty rate is 10%, you get $10. The label or distributor then covers their costs from the remaining $90. This can be good because you get paid sooner, but it also means you might get less overall if the costs are really high.

Here’s a breakdown of how it often plays out:

It’s important to understand that these deals aren't always straightforward. The percentages can be all over the place depending on the services provided, the advance amount, and who has more bargaining power. For instance, physical sales might have a lower royalty rate because they involve more complex logistics than digital sales. Getting a clear picture of these different rates is key to understanding your potential earnings. You can find more information on how artists earn royalties by licensing their artwork.

The specifics of a royalty deal can get complicated quickly. Always read the fine print to know exactly how your earnings are calculated and what costs might be deducted before you see your share.

A consignment contract is pretty common in the art world. Basically, you, the artist, give your artwork to a gallery or a shop to sell for you. You're the "consignor," and the place selling your stuff is the "consignee." They take a cut, called a commission, and give you the rest when your piece sells. If it doesn't sell, you usually get it back.

It's super important to have everything in writing. This protects both you and the gallery. You'll want to make sure the contract clearly states:

You should also think about including a clause that protects your ownership of the artwork until you're fully paid. This is especially helpful if the gallery runs into financial trouble, as it can prevent creditors from claiming your unsold pieces. It's a good way to shield your work.

When you hand over your art, get a signed inventory list back. This confirms they received it and it's now their responsibility. It's a good idea to check out the gallery's reputation and sales history before signing anything. You can find templates and advice on consignment agreements at places that help artists manage their business, like artist resources.

When you grant someone permission to use your artwork for a specific purpose, like on merchandise or in an advertisement, you're entering into a license agreement. Think of yourself as the licensor, giving the rights, and the other party as the licensee, receiving them. It's a common way artists earn money beyond just selling original pieces.

This type of deal outlines exactly how and where your work can be used, for how long, and what you get paid.

Key things to nail down in a license agreement:

Here’s a simple breakdown of payment structures you might see:

It's important to remember that a license agreement is about granting permission, not selling ownership. You retain the rights to your work, but the licensee gets to use it under the agreed upon terms. This distinction is pretty important for protecting your creative assets.

When you agree to create a custom piece of art for someone, that’s a commission agreement. It’s different from selling something you’ve already made because the client is commissioning you to make something for them. This means you need to be super clear about what they want and what you’re going to do.

It’s all about setting expectations upfront.

Here’s a breakdown of what you should cover:

Think of it like this:

A commission agreement is basically a roadmap for a custom art project. It ensures both you and the client know where you're going, how you'll get there, and what happens if someone takes a wrong turn.

This kind of agreement protects both parties. For you, it means you get paid for your time and effort. For the client, it means they get the artwork they envisioned.

When you're talking about deals, especially those involving creative work, the 'Goods or Services' section is where the rubber meets the road. It spells out exactly what you're expected to provide. This isn't just a vague statement; it needs to be crystal clear.

For artists, this could mean a few different things:

The key here is specificity. Vague terms can lead to misunderstandings and disputes down the line. Think about it like this: if you're commissioned to paint a portrait, the contract should state the size, the materials, whether it's head-and-shoulders or full-body, and if reference photos are provided. It’s about defining the deliverable so both parties know what to expect.

Here’s a quick breakdown of what to look for:

Understanding this section is vital for managing expectations and ensuring you get paid for what you deliver. It’s the foundation of any artist client relationship, and getting it right from the start can save a lot of headaches. You can find more information on managing commissions in this guide to professional artist commissions.

It’s easy to gloss over the details in a contract, especially when you’re excited about a project. But the 'Goods or Services' clause is where you define the actual work. Make sure it’s thorough enough to cover all aspects of your creative output and the client's expectations.

So, you've got this deal, and things are humming along. But what happens when you need to get out of it? That's where the termination clause comes in. It's not just a formality; it's your escape hatch. Understanding how to end an agreement is just as important as knowing how to start one. Without a clear termination clause, you could be stuck in a contract longer than you want, or worse, face penalties for trying to leave. It’s pretty common for contracts to just… forget to mention this part, which can really put you in a bind later on.

When you're looking at a contract, pay close attention to how it says you can end things. Does it require you to give a certain amount of notice? Is there a specific reason you need to have for terminating? Sometimes, there's something called a 'cure period.' This means if the other party messes up, you can't just bail immediately. You have to give them a set amount of time to fix their mistake first. It’s like a last chance for them before you can officially call it quits.

Here’s a quick rundown of what to look for:

It’s easy to skim over the termination section, thinking it’s just boilerplate. But seriously, this is where you protect yourself if the relationship goes south. Make sure you know your rights and the process before you sign anything.

So, we've gone over how guarantees and percentage deals work in the music business. It's not always a simple choice, and what's best really depends on your situation. A guarantee gives you a set amount upfront, which is nice for planning. But, if the show or project does really well, you might miss out on bigger earnings with a percentage deal. On the flip side, percentages mean you share in the success, but there's always that risk if things don't perform as expected. Understanding these differences helps you make smarter choices for your career. Always read the fine print and know what you're signing up for.

When you get paid an advance, it's like a down payment for your work. You have to deliver a certain number of songs or a percentage of the album to get the full amount. If you don't hit the target, you might get a portion of the advance, but sometimes it's all or nothing. It's smart to have a deal where you get paid a part of the advance even if you fall a little short, like getting 75% of the money if you deliver 75% of the songs. But, companies usually want you to deliver at least half to get any money.

A floor is the minimum amount you'll get paid, and a ceiling is the maximum. For example, if your deal says you get two-thirds of what you earned last year, but there's a floor of $100,000, you'll get at least $100,000. If the calculation is more than the ceiling, say $200,000, you'll only get $200,000. This protects both you and the person paying you.

A promoter profit deal is a way to split money from an event. First, you figure out all the money made from ticket sales. Then, you subtract costs like facility fees and taxes to get the net amount. Next, you add up all expenses, including the artist's guaranteed payment. The promoter's profit is a percentage of these total expenses. The 'split point' is the amount where the artist gets a bonus. Anything earned above that is split between the artist and promoter, usually with the artist getting a bigger share.

Payment schedules can be set up in a few ways. Sometimes, you get a portion of the money when you sign the deal, another part when you deliver half of what you promised (like songs for an album), and the rest when you finish the job. Another way is to get paid based on your earnings from the previous year, with a minimum (floor) and maximum (ceiling) amount. The timing of payments is important and should be clearly written in the contract.

In a royalty style deal, you get a percentage of the money earned from your music. This percentage can be the same for all types of sales, or it can be different for things like digital downloads versus physical CDs, or for different countries. The contract also says how much of the upfront costs the company can take back from your share. So, even if sales are good, the company might take back all the costs before you see much profit.

A consignment contract is when you let a gallery sell your artwork without buying it outright. You should keep records of everything, like sending two copies of your artwork list. You can negotiate the gallery's commission, usually aiming for 50% or less. Decide if the gallery can offer discounts and who pays for them. Set a clear payment schedule, like getting paid within 30 days of a sale. It's also wise to include a clause that says the artwork is still yours until you're fully paid, which protects you if the gallery has financial problems.

More blogs

Click the button below and finish your organizer registration, or fill out the form and we will be in touch to assist you.